60 mins CPD

Learning Objectives:

- Establishing retirement goals

- Understanding likely changes in retirement

- Illustrating the sustainability of clients’ future lifestyles

- Projecting the potential impact of long-term care

Some clients know exactly what they want to do on the day they retire. Others just know what they DON’T want to be doing (i.e. working)!

Due to the ever-changing and complex nature of the subject matter, this post will be a little longer than previous entries in this series. In this blog, we’ll look at:

- how we can leverage our experience in dealing with retirement cases to coach clients towards a better understanding of what their financial futures look like?

- what potential pitfalls we need to be aware of

- is there any such thing as a “typical” retirement, and what defaults (if any) should we be assuming?

- how do we factor in the potential cost of long-term care?

Expert Insight

We’ll look at all of the above in detail below. For now, here’s how some of our customers encourage their clients to think about what they really want to get out of retirement.

Retirement Spending

Why is it important?

The most important part of any financial plan is expenditure. More specifically, it’s the difference between expenditure and income. If clients don’t know what shape their retirement is likely to take, how can we help them plan for it? Clients might have a perceived “income need” in retirement. They might be trying to establish whether a certain level of pension income is acceptable. Without understanding their goals and needs, it’s impossible to give robust advice.

Having an accurate grasp of clients’ spending needs throughout the various stages of retirement then allows us to address sustainability. Clients can’t spend more than they have and making sure their pensions, investments, and savings don’t run out in retirement is a key aspect of retirement planning.

This is why cashflow modelling must be driven by expenditure, not income. Telling clients “your pensions can give you an income of X” is placing the cart before the horse. By helping clients understand the likely costs of their desired future lifestyle, throughout its various stages, we can establish whether their goals are realistic and achievable.

The software we use then helps us create a plan that facilitates this lifestyle. But it’s only by understanding the expenditure required to fund that lifestyle that we can help them make informed decisions towards realising their objectives.

Here be dragons

However clear (or unclear) your clients future plans might be, remember: they have never retired before. In this field, at least, you will definitely have more experience than them.

Many clients will have “plans” for retirement; others will just want to stop work. In either case, there’s a big gap between having retirement goals and having an understanding of what “the rest of your life” could really look like.

In an earlier post, we looked at average life expectancies and for how long our cashflow models should project. The general consensus is that 100 is a sensible point to end our models. In other words: “the rest of your life” for a client retiring at 55 could potentially be 45 years.

If you could travel back in time and speak to one of your clients as a 10-year-old, do you think they could tell you what they wanted the entirety of their working life to look like? Asking clients approaching retirement what they want to get out of the rest of their lives is fundamentally no different to asking them to plan up to retirement at age 10.

As they venture forth into the unknown, how can we leverage both our own experience and data from generations of retirees better to inform them and prepare them for what might be around the corner?

The Shape of Retirement

There have been a number of theories published about the “shape” of retirement. All of these hold water for certain clients, but none are universal. Your client’s retirement might be “U-shaped” (expensive early on; cheaper in the middle; expensive in later life), it might be “tiered” (starts expensive, gradually reducing), it might be something else entirely.

The true shape of retirement will vary significantly from client to client, but will almost certainly follow trends. Research has shown that these trends occur irrespective of the level of client wealth. So what general “rules of thumb” exist, and how can we apply these to our cashflows?

Early Retirement

Some clients assume their costs will fall and life will be cheaper when they retire, but it almost certainly won’t be. While there will almost certainly be an income tax saving in retirement, the idea that costs will suddenly drop when they reach retirement is generally a misconception. Mortgages might go and kids might become independent, but other expenses arrive to replace these.

Discretionary spending on things like socialising and holidays will almost certainly increase. Even if the overall level of spending remains the same, being able to illustrate this to clients will help them understand why life doesn’t suddenly become cheaper.

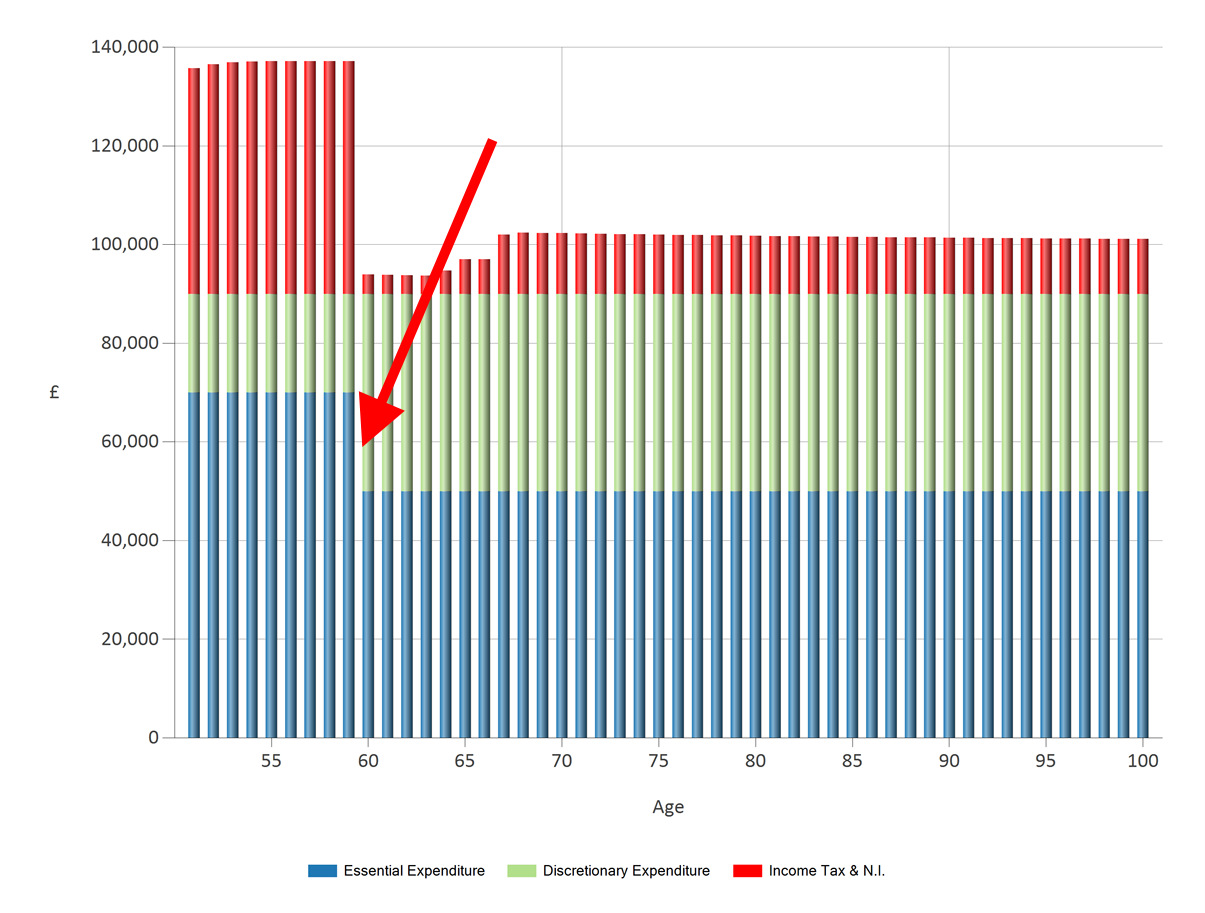

For example (as shown in this chart) a client might be spending £90k a year pre-retirement, of which £70k is “essentials” (bills, housekeeping, commuting, mortgage fees, etc.) and £20k is “discretionary” (holidays, eating out, socialising, etc.). When they retire, the reduction in “essential” spending is often met by an increase in “discretionary” expenditure.

Which? published a fantastic article earlier this year looking at the potential cost of retirement for clients with “Essential”, “Comfortable” and “Luxurious” aspirations. I’ve included a link below (as well as borrowing their infographic) as it’s a great place to start for clients who might have no idea what retirement might look like.

Source: https://www.which.co.uk/money/pensions-and-retirement/starting-to-plan-your-retirement/how-much-will-you-need-to-retire-atu0z9k0lw3p

Permission to spend money

Here’s where your experience comes into play. You can’t make any “default” assumptions about what the early years of a client’s retirement will look like – it’s highly personal to each individual. Do they want to travel more? Do they want to lavish gifts on the grandkids? Do they want to buy a campervan and spend 18 months driving around Europe?!

Talking with clients about their plans for retirement is a matter of coaching and asking probing questions. Often, clients need to be persuaded to have fun and enjoy the money they’ve spent years putting aside.

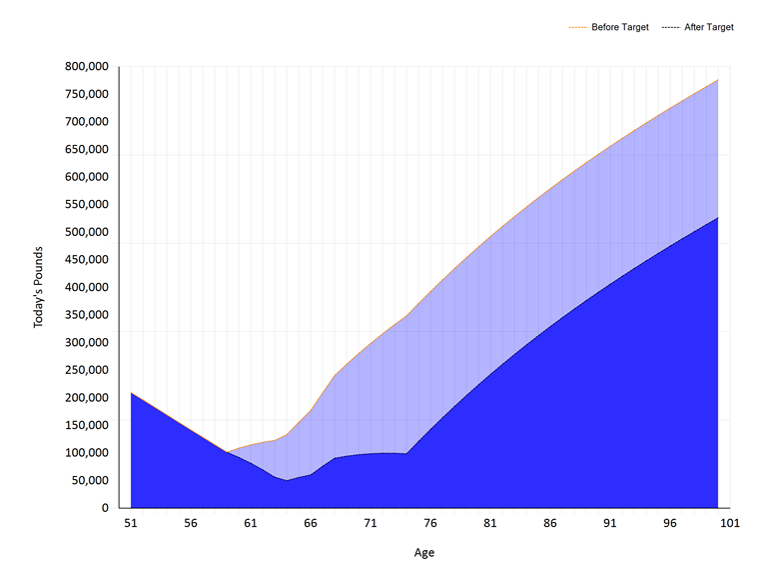

A cashflow capital chart in Truth illustrating the client’s liquid capital projection with and without significant additional expenditure

We run regional User Groups around the country, which give Truth® users the opportunity to get together and talk about best practice. At one of these meetings, we talked about our “More Expenditure” tool. One of the attendees mentioned that he uses this with all clients whose cashflows show their wealth growing over time. He’ll show them their cashflow, which ends with them having far too much money. Then he’ll use the tool to illustrate how much more they could spend in early retirement (without running out, of course) and ask the client what the difference is.

His client meetings (pre-COVID) were held in his meeting room, where cashflows were presented on a huge screen along one side of the room. At this point, clients would inevitably get out of their seats and examine the scale of the chart and the tangent of the two lines.

Clients will “umm” and “ahh” for a while, before replying with a number – “the difference between the two lines is £300,000.” To this, the adviser replies “No, the difference between these two lines is opportunity.” Yes, the top line is all the wealth they could accrue, but the bottom line shows they could do considerably more with their lives than they might currently have planned, all without ever running out of money.

Paul Etheridge used to include a ‘wild living’ allowance for his retired clients, in an effort to encourage them to enjoy their money. He received postcards from all four corners of the globe from clients with ‘wild living’ written on them. One of his clients, an elderly lady with no dependents, decided that rather than go into a care home she would sell everything and became resident on a cruise ship for £4,000 a month. For that, she had chefs, cleaners, doctors, the company of other people… and fun!

Later Life

At some point, the pace of life catches up with us all. There will often be a point in clients’ lives when the stresses and worries of boarding a long-haul flight outweigh the rewards of arriving at their destination. At the same point, they will likely stop wanting to climb a ladder and paint the kitchen ceiling or fix broken gutters. Clients might stop driving, but the cost of running their cars will be replaced by taxis…

If you watch the video interview that accompanies this blog, you’ll see that some of our customers allow for a reduction of between 30 and 50% in discretionary spending in later life.

Just like at retirement, when mundane expenditure is often replaced by more aspirational stuff: when discretionary spending falls in later life, spending on services often rises to meet it. Indeed, the cost of later life can even exceed the cost of early retirement. It’s at this point that sustainability becomes a factor for many clients. Having achieved the majority of their objectives, are our clients’ remaining funds sufficient to fund the (less enjoyable, but equally essential) costs of later life?

This period in clients’ lives is also often the point at which they will consider more considerable gifts. As with spending in early retirement, many clients need coaching, persuading, or permitting to use their money as a force for good. Helping clients to understand that they can afford to gift with a warm hand, rather than a cold one, can be hugely powerful.

When will the “heyday” end?

The question is when will this reduction occur? As one of the interviewees says – “if I were to offer you an all expenses paid trip to New Zealand, at what age would you say no to it?”

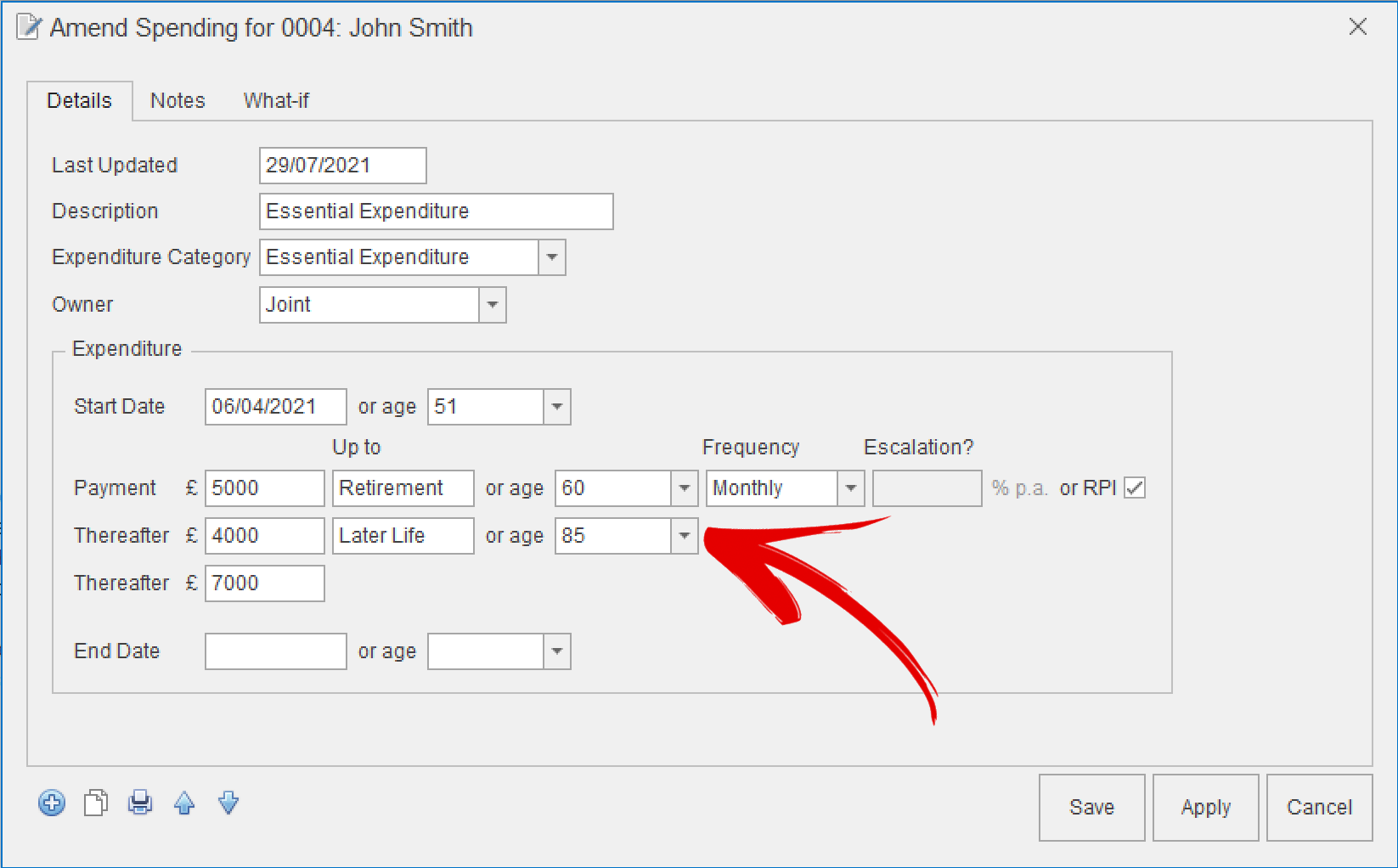

One of the best ways of illustrating this in Truth is through the use of Key Dates. Key Dates are dynamic lifestyle events that allow you to simultaneously adjust multiple assumptions in your model. For example: we can tie the point at which Essential Expenditure starts, stops, increases, or decreases to a Key Date (or Key Dates). In this example, my client is spending £5,000 a month on “Essential Expenditure” up to a “Retirement” key date. From “Retirement” to “Later Life”, this drops to £4,000 a month. In “Later Life”, this rises dramatically to £7,000 a month.

This example is deliberately simplified. We advocate going into far more granular detail on clients’ spending as this dramatically increases their engagement with the process as discussed in this blog post. The point here is that we can “bookend” the heyday of retirement with key dates and move these around during a meeting to illustrate the impact of changing these dates.

Key Dates can control not only expenditure but also when pension contributions start and stop; when clients access their pensions; when they sell assets, or when they start taking income from investments.

As with changing costs, when it comes to the duration of different periods of retirement clients will often defer to your experience. Remember: you’ve dealt with countless retirees, but they themselves have never retired before! Being able to vary this during a meeting, or to show clients a picture of what it might look like if “active retirement” lasted to 75, 80, or even 90 makes conversations about retirement spending less academic and more dynamic. You’re working together to create a picture of their retirement lifestyles, incorporating all their goals and objectives and seasoned with your ex

perience and reasonable assumptions derived from statistical analysis. The result: a robust, collaborative model, designed to set clients’ minds at ease.

Long-term Care

One of the most important (and often overlooked) aspects of retirement planning is the potential costs of care. It’s one expense that many clients don’t plan for, and showing them that their cashflow is resilient enough to accommodate care costs can provide a huge amount of reassurance.

Costs

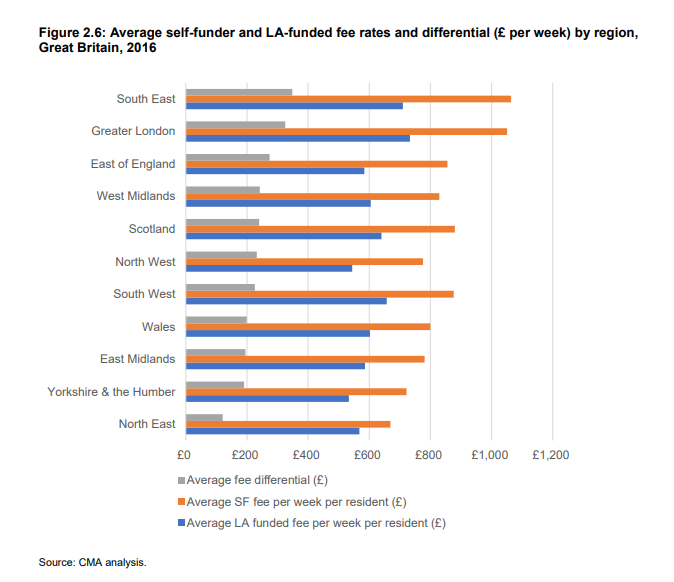

The cost of care varies massively depending on geography and on the type and quality of care clients require. The CMA analysis included under further reading below gives some indication of the geographical variance. In London, self-funded care can easily exceed £1,000/week – nearly double the equivalent cost in the North East.

Numerous sources, including Carehome.co.uk quote current average monthly costs between £2,800 and £3,500.

Clients may know of local care homes. They may have visited relatives or other residents, and might have an opinion as to the kind of place they would want to live in, should the need arise.

One approach that works particularly well is making enquiries with care homes in your local area to get an idea of likely costs. Where clients might have no preconceived ideas about care costs, being able to recommend options and give a realistic illustration of costs can provide further reassurance.

Having established not only the cost of “care”, but the cost of a standard of care your clients might be happy to live with, we can build this into their cashflow models.

Escalation

As we discussed in our recent post on how to incorporate inflation in cashflow models, there are certain costs that generally rise above inflation. Among these, school fees and the cost of care are two which are almost guaranteed to grow well above inflation.

Recent research by Which? indicates that the costs of residential care have increased by nearly 5% year-on-year for the last two years. Over the same period, inflation hovered around 2% – in other words, the cost of care escalated at inflation +3%. Depending on your chosen inflation rate, modelling care costs at anything between inflation +2% and inflation +4% would be entirely justifiable. Of course, the higher the escalation you assume, the more cautious your model will be.

Duration

There have been a wide range of studies into the average duration of care, or life expectancy in care homes. ONS figures show that 4-5 years might be a reasonable assumption; I’ve seen studies suggesting less than 2 and more than 7. But you should bear in mind that these figures are often based on those arriving at care from hospital. Clients moving into care or assisted living voluntarily could reasonably expect to live up to or beyond “average” life expectancy (see our recent post on longevity).

If you’re going to factor in fixed-term care costs for a client (e.g. 2 years, 5 years, even 10 years) at what point do you stop?

In Truth, you can use Key Dates (as we looked at earlier with changes to expenditure) to incorporate care costs for any length of time. This approach can help illustrate to clients at what point their cashflow might “break”. For example: their capital might be able to sustain 15 years’ worth of care costs, but not 20 years’ worth of costs.

Just like running a Market Crash, this is just another way of stress-testing the robustness of our model.

What is reasonable?

While every client will be different and it’s crucial that their cashflow model reflects their own plans and objectives, there are some sensible defaults or rules-of-thumb that we can use to advise those who might not know what they want from their retirement.

While every client will be different and it’s crucial that their cashflow model reflects their own plans and objectives, there are some sensible defaults or rules-of-thumb that we can use to advise those who might not know what they want from their retirement.

In general, costs rarely reduce at retirement and often increase. The assumption that life will get cheaper is largely based on perception but rarely becomes a reality. Instead, it’s how and where money is spent that tends to change. Savings on mortgage costs or school fees tend to be replaced by more adventurous holidays or higher spending on holidays.

In later life, costs may gradually start to decrease. Once again, there is generally a change in spending patterns: holidays may be replaced by staycations; the cost of flights replaced by the cost of services. Clients may stop driving and start taking taxis. This time, however, this shift often equates to an overall reduction in spending. One common approach is to model a reduction of around 25% in later retirement.

As a number of interviewees mentioned in the video below, it can be prudent to incorporate a second shift in spending later on. If clients are still alive at 85 or 95, would they still be spending at the same rate as they would at 75?

Of course, the smaller the reductions in retirement spending, the more cautious your cashflow. Assuming expenditure is unchanged (or even increases) in later retirement would result in a very pessimistic model but might be appropriate depending on your client’s individual circumstances.

Modelling increased costs towards the end of your cashflow (such as the cost of care) can be a useful stress test, but is unlikely to be reflected in reality. Research from Laing Buisson and others indicates that the need for residential care in later life is the exception, rather than the norm. Only around 4% of over-65s live in care homes, rising to 15% of over-85s. Unless clients have a specific reason for expecting to need care, incorporating the costs of care into their cashflow as a default may be overly-pessimistic.

Remember, the goal is not to shock clients, but rather to pre-empt potential problems and provide reassurance. Showing the impact of a market crash is no different to projecting up to age 100 for a client whose life expectancy may only be 87. By going beyond what might reasonably be expected, we’re simply stress-testing the client’s strategy and providing robust financial advice.

Further reading

The following are useful resources when deciding on and documenting your assumptions and the reasoning behind them:

Which: “How much will you need to retire” analysis

Boomers: Redefining Retirement by Marlene Outrim

Sun Life: “An Insight into the Cost of Retirement”

ONS: Life Expectancy in Care Homes

CMA: Costs of Care market study (see p.44 for geographical costs of care)